Mary-Rose Puttick

Birmingham City University

Over the next few months, BALID will bring you a series of blog conversations following BALID’s last interactive Informal Literacy Discussion (ILD) on the theme of ‘applying visual and sensory literacies in refugee research and practice’. Taking some definitions of visual and sensory literacies as a starting point, the blog series will look at further examples of its use in research, teaching, and arts practice, as well as raising important considerations around ethics, voice, and agency.

Attuned to the interactive and dialogical nature of the ILD, in this introductory blog, Mary-Rose revisits some key aspects of the event, interwoven with a set of visual artefacts, and uses this as a stimulus for thinking and ‘putting to work’ some of the ideas from her co-presenters Arianna Berardi and Katie Blair: applying them to her distinct, yet interconnected, research assistant and volunteering roles.

—

The ILD opened with a visual artefact that, for me, symbolises the start of my doctoral research and my move to a new city. Perhaps heightened by its location under a grey concrete bridge on the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, as well as the temporal circumstances of a new chapter in my life, the ‘Welcome to Birmingham’ street art always gave me a sense of comfort when I cycled past on my way to the Somali community centre and never failed to bring a smile to my face (and still does).

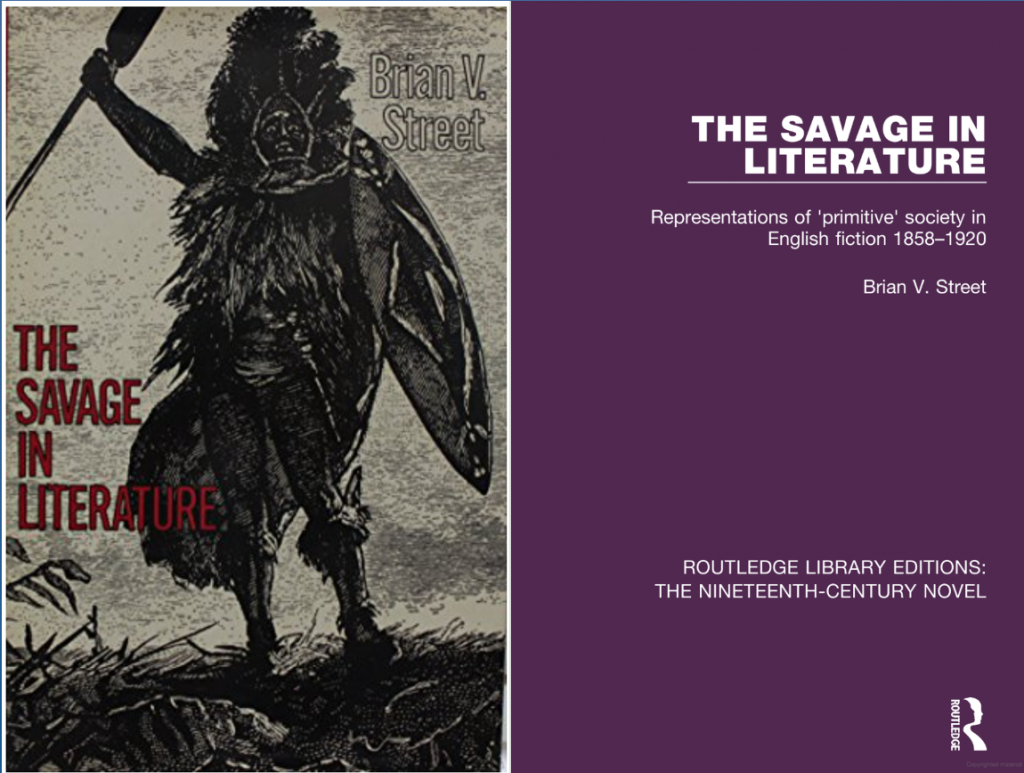

I continued to give an overview of some key definitions in visual literacies, to which I keep returning. Rowsell defines visual literacy as ‘the ability to make meaning from information in the form of the image’, recognising the competence or the ability of the ‘reader’ of the image ‘to interpret, evaluate, and represent the meaning in visual form’ (2012: 444). Important also in my participatory ‘reimagining family literacy’ research with two groups of women, upon which I based my ILD talk, is the ‘artifactual literacies’ work of Pahl and Rowsell (2010): this work has helped me to think about how artefacts evoke memories and how they embody places, movement, intergenerational stories, feelings, memories, and communities. Thinking with embodiment, I now revisit some of the key aspects from my co-presenters, Katie and Arianna.

‘Thinking through the linguistic landscapes of Covid-19’

Katie Blair’s interactive digital walking tour through the Southern Italian town of Riace gave us a fascinating insight into her doctoral research and what she has conceptualised as the ‘Solidarity-Scape’ (read the second instalment of the series to learn more about Katie’s work). Seeing all those vivid community artefacts and visual signs inspired me to think about the linguistic landscapes of the two areas of Birmingham that I volunteer in, with the ‘Welcome’ sign above being part of one of these, and to think about the affective power of these representations.

I considered how I could re-enact Katie’s interactive walk with the families I work with from newly arrived and refugee backgrounds. Taking them on an interactive walk of their local areas could support families to feel a sense of belonging to their area by sharing in dialogue about the linguistic landscape of their new, and for some very temporary, ‘home’ and to learn multi-modal, and multilingual, ways of expressing welcome and solidarity. As well as thinking about the possibilities of linguistic landscapes in spatial dimensions, I also thought about how they can be applied to specific moments or periods in time, particularly considering the ephemeral nature of some of the street art of cities.

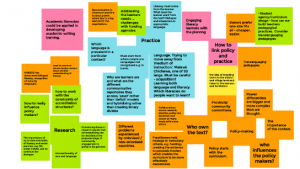

As I am currently working as a research assistant on the ‘Collaborative Community Mapping’ (Co-MAP) Erasmus+ project which explores how young people navigated diverse forms of learning during the Covid-19 school closures, I decided to try applying some of the principles of Katie’s approach to the research context of the Co-MAP project.

Scanning the hundreds of photographs I took on my walks of the city during the period of lockdowns, I found numerous images of the rainbow, in multiple abstract forms, that came to symbolise public gratitude to the UK’s National Health Service during this time: the rainbow would certainly feature on my Co-MAP linguistic landscape. However, there are two special images that I will always associate with that time of my life and historical moment: both of which, to me, embody the notion of ‘solidarity’. I considered the two visual artefacts with some of the questions that Katie raised in the ILD as stimulus: how do they make you feel? what impressions and reactions are you getting from these now?

These ‘Posters of Positivity’ became a surprisingly important mental health support to me during the Covid-19 lockdowns. I was immediately struck by the combination of the bright colours and the powerful directness of the messages. As time went on, I started to find more of the posters in different parts of the city, often in unexpected places such as in rundown backstreets. Every time I encountered one of the posters it sparked some excitement in me as I took a new photograph to add to the positivity trail I was imagining across the city. The posters gave me a sense of a collective, community mantra that brought people together during deeply challenging times.

The second artefact was particularly special as I saw it being created in action by street artist Gent 48 and also had the opportunity to speak to the artist. I was transfixed by the scale of the work and to see it emerging before my eyes. I was not only learning about the process of creating a large-scale art piece, but also was privileged to learn about the artist’s thinking behind the piece. To me, the entire image encapsulates the coming together of key workers and communities against this invisible, persistent, and dangerous force. When I now look at the visual artefact, it gives me a renewed sense of respect for all of the frontline workers that put themselves at risk to help others: a poignant feeling that has deepened now that I look at this two years later, at a different point of the pandemic, knowing what has happened in the ‘time and space between’.

‘Reimagining through rhythms’

I am using my final visual artefact as a stimulus to revisit Arianna’s interactive activity (see Arianna’s forthcoming blog to learn more). Hearing about Arianna’s music therapy work with refugees, and wider community members, was deeply moving, particularly her spontaneous approach that is unique and adaptive to each group she works with. Watching the way that she integrated her interactive activity into mine made me think about sensory literacies in ways I hadn’t considered before. Following my ‘sensory intra-action’ in the ILD where I asked the audience to recollect a smell that conjured up a particular memory of a place or time, Arianna asked us to revisit this memory. She invited us to add a rhythm to our memory: using an everyday object around us, and later demonstrated how she would vocalise her own olfactory memory associated with her grandmother’s house.

Recently I went to visit the women at the Somali centre and one of them, Zainab, had the most beautiful henna (which she told me was ‘xinaha’ in Somali) design painted on her hands and arms ahead of a wedding that she was going to at the weekend. Although I had seen henna many times before and loved the different designs I had seen, hearing Zainab and the other women talk collectively about the meanings of the henna in terms of gendered and cultural traditions added to its beauty. Later I started to think about Arianna’s work and about how the women might interpret the process of henna rhythmically and vocally: how would the feelings of family and cultural histories that are embodied within the artwork sound? How would the sounds come together in a collective: in women’s solidarity? Does henna have a particular smell attached to it and how could that smell sound?

Future thinking

I would like to draw my reflections to a close with a few important reminders. Sensory activities can unearth potentially emotive, or even traumatic, memories and therefore what remains of utmost importance throughout is to cultivate an inclusive, agential space in which all individuals are invited to participate, yet do not feel under any obligation. Sensory sharings must be accompanied by a respectful, caring, and ethical dialogue that involves refugee participants in decision-making around what sensory activities might look like and with whom they are shared.

Finally, at the end of the ILD, we explored some prompt questions in breakout rooms and two websites were kindly contributed by participants. I am looking forward to exploring the websites further and to continue learning in the area of visual and sensory literacies:

- https://www.leslla.org/resources-in-mother-tongues (contributed by Ian Cheffy)

- ALEF, a Swedish adult literacy organisation working in Togo, the Congo, Uganda and Ethiopia! https://en.alef.org/om-oss (contributed by Margareta Langbacka Walker)

References

Pahl, K. and Rowsell, J. (2010) Artifactual literacies: Every object tells a story. New York: Teachers College Press.

Rowsell, J., McLean, C. and Hamilton, M., 2012. Visual literacy as a classroom approach. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(5), pp.444-447.

—

Mary-Rose Puttick is a Research Assistant at Birmingham City University, working on the Erasmus+ Co-MAP project. Her British Council project ‘Waiting for School’ is exploring educational provision for children from asylum seeking backgrounds between UK arrival and school. Mary-Rose’s PhD, completed in 2021, focused on family literacy provision in the refugee third sector.