Professor Alan Rogers served BALID as President from 2020 but before that he had been an outstanding supporter and ‘critical friend’ for many, many years! We will miss Alan’s enthusiasm and energy not only on literacy and development but adult learning in general. In this blog post, BALID committee members share their memories and tributes to Alan – celebrating his impact on many of us over the years!

Chris Millora, BALID Chair

Adapted from a tribute Chris read during Alan’s funeral service on 22 April 2022 at Southwell Minster.

Alan once told me a very useful analogy when I was having a hard time writing my thesis. He said that I could imagine my thesis as exploring a house. Now, I am going to discuss the kitchen and the dining room and their relationships, not the whole house, because I do not have enough space to write about the whole building. When I was writing this tribute and reading the many good words from colleagues about Alan, I was once again reminded of this analogy. I can certainly not capture the vastness of Alan’s impact to me as his former PhD student and to us at BALID. We at BALID greatly benefited from Alan’s incredible support, wisdom and commitment as a colleague and friend. As a tribute, I can only share some of this impact – just a couple of rooms in the big, beautiful house that Alan has helped built over the years.

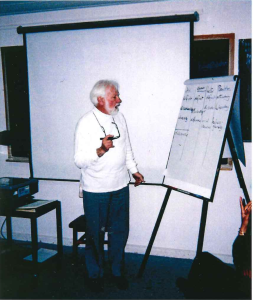

Alan was a long-time supporter and critical friend of BALID. He served as committee member for many years and in 2020 was elected President. Many of us at BALID remember Alan’s intellectual energy. He often challenged our fundamental thinking around literacy – especially at a time when we were expanding our membership to include international partners in the Global South, some of whom such as our colleagues in Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Uganda, drew from Alan’s scholarship. I can also remember how Alan spoke so enthusiastically about a fantastic programme BALID used to conduct for many years during the Easter university vacation – gathering students from the Global South doing PhD research in the UK for a week of engaging with each other and with literacy scholars and experts in the field. When I heard this, I knew his heart had always been in supporting future scholars and facilitators in the field.

I knew Alan personally as my PhD supervisor. Having read much of his work, I was in awe of his wisdom and his humility and commitment to supporting young scholars. I can still remember vividly our first meeting. Anna, who was my primary supervisor, explained that she would be giving 80% of the supervision and Kate, my second supervisor, would give 20%. Alan, who was part of the team on a voluntary basis, remarked something like, “And I will be giving another 100%. So, you have 200% of our support!”. And it did feel that way – mentorship that went over and beyond the writing of a thesis. A year before I finished my PhD, Alan encouraged me to accept the invitation to be BALID Chair – a change in their leadership after 15 years and a decision that has helped me grow personally and professionally. In fact, I was unaware of his declining health because he had been so active giving comments to my book proposal for a series which he and Anna Robinson-Pant were co-editing. I signed the contract last month and it is a great pity that Alan will not be around to read the final product.

I’d like to think that Alan did not only ‘teach’ us something, but he ‘helped’ us. He was always generous with his time and ideas – and was very open to listen and give advice. Last December, Alan wrote a thought-provoking piece in the BALID blog which powerfully explained his distinction between teaching and helping. And I’d like to close my tribute today by sharing part of Alan’s blog:

It may seem strange that I – who have for years been researching and teaching about adult learning – should say that we should stop talking about learning and teaching and instead talk about helping. But let me assure you that, if you really sit beside someone and with their willing assent help them with their tasks (like helping a child with their homework), the adult will learn much more than if you try to teach them. It is a very simple change to make but it starts with us, not with the facilitator or the ‘learners’. No more ‘teaching’, just helping. And helping people with their tasks is so much more rewarding than teaching them something we think they should learn. At least, it is worth a try.

Katy Newell-Jones, former chair of BALID

Alan generously planted seeds, showed people opportunities and threw out challenges.

I first met him in 1992, when he was coordinating the NGO Education for Development and needed free space for some workshops for literacy practitioners from Egypt. At the end of an inspiring week, Alan asked if I had ever thought of supporting literacy overseas. No, I hadn’t, but he planted the seed, showed me the opportunities and threw me the challenge.

As well as supporting early career researchers, Alan also supported early career facilitators. He promoted participatory approaches, actively encouraged participants to discuss in languages in which they felt most comfortable, and questioned facilitators’ motivation behind needing to follow every conversation. Again, seeds, opportunities and challenges.

During my time as chair of BALID, Alan provided valuable links to early career researchers and input into key events. I am reminded particularly of December 2019, when he gave the closing comments at the Brian Street memorial event Literacy as Social Practice, hosted by BALID, the UNESCO Chair in Adult Literacy and Learning for Transformation, and King’s College London (See here for the report of the meeting.) The room was buzzing with energy. The event had been highly engaging and interactive. Alan had three points which he shared in characteristically clear, direct language, referring back to seeds planted long ago, like “literacy comes second”[2] (see Alan Rogers, 2000, “Literacy comes second: working with groups in developing societies”, Development in Practice 10.2, pages 236-240).

- I came to wonder if sometimes we are as much part of the problem as we are the answer to the problem.

- What matters?

- ‘Them’ and ‘us’

I am grateful for the immense learning which resulted from opportunities to engage with Alan, and the legacy he has left for us all to continue to develop and learn in the future.

Ian Cheffy, SIL International, BALID Treasurer

Although Alan was a committee member I recall that it was difficult for him to travel to London for our face-to-face meetings which were the norm in those pre-Covid days so his contributions were largely by email. He was certainly keen to keep us on track, and I recall that he could be quite challenging at times! The phrase “critical friend” comes to mind!

He was certainly passionate about adult education, and it was interesting to see how his interest in adult literacy in development led to him collaborating with Brian Street on the LETTER project, introducing literacy practitioners in several countries to the approach to literacy as a social practice. I very much appreciated his desire for adult literacy teachers and facilitators to recognise the actual uses of reading and writing which were important to people and to design teaching programmes around those. Such an approach is vitally important but I regret that it has not made the impression that it deserves.

Alan was committed to helping people grow. I was particularly glad of his support which was instrumental in the publication of the BALID book “Theory and Practice in Literacy and Development” edited by Juliet McCaffery and Brian Street (see McCaffery, J and Street, B (2016) Theory and Practice in Literacy and Development: Papers from the BALID Informal Literacy Discussions BALID and Uppingham Press)

Alan was a pioneer with a deep commitment to the study and the practice of adult education. He was an initiator too – here I am thinking of his Uppingham Seminar series, which he organised and which were held in a thoroughly collaborative manner. I attended only the one in 2016 but it was fascinating to see how he had been able to bring together a number of significant people in our world of literacy and development including some from UNESCO as well as literacy leaders from other countries.

We will miss Alan in person but his influence on our thinking and practice will not disappear.

Suzan Voga-Duffee, Rift Valley Institute, South Sudan

It was Katy Newell-Jones who introduced Alan to me. At the time he was trying to get in touch with a group of South Sudanese who were conducting research for him. Katy put us in touch hoping I might know some of the students and could let them know that Alan was trying to contact them. It so happened that the same students got in touch with him while we were still emailing back and forth.

I immediately knew Alan was a good man with a golden heart, because he started to ask me what my interests were and if I was interested in academia, to which I said I was. He wanted to know my educational inspirations and asked about my work and we ended up discussing my Master’s thesis. He suggested I publish it, with his help of course. We had planned on how to do this, with him sending me guidance on how to rewrite the thesis. I am now in the process of editing it…and then came this news of his demise. May his gentle soul rest in peace.

Mary-Rose Puttick, Birmingham City University

Sadly, I didn’t get the chance to meet Alan in person. However, I feel lucky that I have had email correspondence with him over the last year when he gave me the opportunity to write a chapter for his forthcoming book with Jules Robbins. Alan was very kind and supportive to me throughout this process.

Gordon O. Ade-Ojo, University of Greenwich

Really devastated by this news, as I have only this week realised that Alan had invited me to contribute a chapter to a book he was editing but somehow the email had been ‘junked’. On Wednesday, I was just going to delete all the mails in my ‘junk’ and, for some reason, decided to take a quick look and found the email he had sent to me back in 2021. I now feel that I missed the opportunity of associating with greatness.

Talking about greatness, that exactly describes Alan. I had recommended his books and other contributions to my students for decades and was totally in awe when I finally met him in person. For such a great man, so much humility and readiness to interact with mere mortals like me. A sad day for the academic community in general, and for those he has admitted into his academic family.

True greatness in academia is never transient. It endures forever. Rest in peace, Alan

Shaida Salwi is currently the Head of Department for the Primary Unit, and an English educator at Victoria International School, Malaysia. She is also studying for an MA in English Literature at the University of Malaya. She is very passionate about female empowerment, children’s education and folklore. You may find her on Twitter @shaidaslwi

Shaida Salwi is currently the Head of Department for the Primary Unit, and an English educator at Victoria International School, Malaysia. She is also studying for an MA in English Literature at the University of Malaya. She is very passionate about female empowerment, children’s education and folklore. You may find her on Twitter @shaidaslwi

Yeonhee Sun is currently working as Youth Development Lead at The Prince’s Trust in the West Midlands, United Kingdom. She completed her MA in Education and Development from the University of East Anglia and has been involved in Rwandan adult literacy education through the Bridge Africa Project from the Korean National Commission for UNESCO. She also coordinated educational programmes with volunteers in Rwanda. Email: Yeonheesun1@gmail.com; Twitter: Yeonhee_Sun

Yeonhee Sun is currently working as Youth Development Lead at The Prince’s Trust in the West Midlands, United Kingdom. She completed her MA in Education and Development from the University of East Anglia and has been involved in Rwandan adult literacy education through the Bridge Africa Project from the Korean National Commission for UNESCO. She also coordinated educational programmes with volunteers in Rwanda. Email: Yeonheesun1@gmail.com; Twitter: Yeonhee_Sun

Janelle Rabe is a doctoral researcher at the Durham University Department of Sociology and a member of the Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA). Her PhD project is funded by the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership (NINE DTP) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). She has a decade of experience working with non-governmental organizations and policymakers in the Philippines on child rights and development issues. She has contributed to policy advocacy campaigns leading to the passage of laws on raising the age of sexual consent, child nutrition and child protection.

Janelle Rabe is a doctoral researcher at the Durham University Department of Sociology and a member of the Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA). Her PhD project is funded by the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership (NINE DTP) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). She has a decade of experience working with non-governmental organizations and policymakers in the Philippines on child rights and development issues. She has contributed to policy advocacy campaigns leading to the passage of laws on raising the age of sexual consent, child nutrition and child protection.

Zubair

Zubair

Arianna Berardi. I am a musician and music therapist working for Nordoff Robbins, the largest independent music therapy charity in the UK. I have a background in Psychology and in the performing arts, and I began working as a music therapist in 2021. I am currently working in a variety of settings including special needs education, adult mental health, and refugee organisations.

Arianna Berardi. I am a musician and music therapist working for Nordoff Robbins, the largest independent music therapy charity in the UK. I have a background in Psychology and in the performing arts, and I began working as a music therapist in 2021. I am currently working in a variety of settings including special needs education, adult mental health, and refugee organisations.