Shaida Salwi

Victoria International School, Malaysia

Over the next few months, BALID will host a series of blogs exploring the role of informal learning and literacies in young people’s everyday lives. The series hopes to feature young people’s work and ideas, inspire intergenerational conversation and become the basis for future action / research in these areas. Learn more about the series here and how you can contribute. More blogs in the series can be found here.

In this post, we hear about reflections from Shaida Salwi, an English teacher of an international school in Malaysia. She writes about her observations of the challenges and potentials of digital technology in the classroom and beyond – particularly among young people.

In today’s digital era, specifically looking at Malaysia, the learning landscape is moving (albeit at a snail’s pace) towards the transformation that we desire. Students who are living in urban areas are increasingly reliant on technology for various aspects of their lives, including education and identity exploration. In contrast, indigenous students draw on their community-embedded traditional knowledge for experiences. As a young educator who teaches students who live in urban areas whilst also volunteering my time teaching in rural areas, specifically the indigenous communities, I’d like to open a conversation on the different ways students from urban and rural areas learn informally through technology and indigenous practices and how it can impact their self-identity.

Digital platforms, educational apps, and various online resources have been growing lately in schools in Malaysia. It not only benefits us educators, but also helps students in urban areas who have seamlessly integrated technology into their lives and have been using these tools to expand their knowledge and skills. The digital divide in Malaysia is evident when I compare students who reside in urban areas to students who live in rural areas especially those of indigenous communities. While students in urban areas often have greater access to technology and digital resources, students from indigenous communities face barriers to technology access, resulting in a disparity in digital literacy and opportunities for self-directed learning. From educational YouTube channels to interactive learning applications such as Kahoot or Quizizz, students in urban areas have access to a wealth of information and engaging learning experiences. The benefits of technology-enabled informal learning include personalised learning opportunities and the ability to explore a wide range of subjects beyond the confines of the traditional classroom.

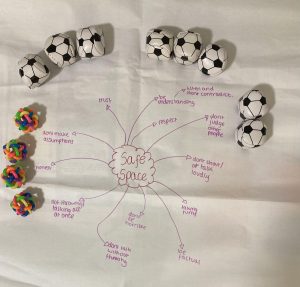

In our school, we teach Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) as a form of self-directed learning to prepare the students for the reality of life outside of the classroom. In the above picture, I brought the students to the school’s computer lab to work on their project which is related to their self-identity. There are three parts to the activities which include creating vision boards, personal narrative writing, and engaging in self-reflection exercises. These activities aim to empower students to explore their unique identities, build self-confidence, and cultivate a sense of authenticity and self-awareness. Being a Malaysian means you are part of a melting cultural pot. For these students, their identity is very important to them and they understand that it is crucial to learn how to navigate life based on their identity as their choices can make or break society. The autonomy and flexibility of technology definitely helped my students to achieve their goals but my concern lies in their increasing dependency on technology which may cause more harm than good.

When students in urban areas become solely and too dependent on technology, I believe, this may limit their exposure to real-world experiences which includes physical interaction with the environment, hands-on activities, and practical learning opportunities that are crucial for holistic growth. Relying excessively on virtual simulations or digital resources may restrict their understanding of the real world.

Let’s have a look at the other side of the story: in contrast to the technology-driven approach, I have observed some students who live in rural areas, specifically the Malaysian indigenous students, draw on community-embedded traditional knowledge and values for their experiences instead of relying too much on technology. Within their communities, intergenerational knowledge is often transferred to them via their elders who play a vital role in shaping their self-identity. Plus, students from indigenous communities actively engage with their environment, connect with their heritage, and immerse themselves in the cultural fabric of their communities. Thus, compared to their urban counterparts, I observe that the apparent stronger emphasis on experiential and hands-on learning, oral traditions, and observation of cultural practices majorly contributes to their holistic understanding of the world.

(Pictures taken by Shaida and her team)

In my view, students who live at a distance from the internet have the best of both worlds in the sense that they are not totally dependent on technology, unlike some of those who live in urban areas. I’m not saying that there shouldn’t be room for expanding the usage of technology in indigenous students’ lives. In fact, there are students who live in rural areas and those who come from indigenous backgrounds who are savvy in using social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram and the like. Thus, I’m positive that digital tools can be employed to preserve and share traditional knowledge, ensuring its transmission to future generations. I can imagine that digital storytelling, multimedia presentations, and online platforms may provide opportunities for indigenous students to showcase their cultural heritage and further engage with wider audiences as per my observation while volunteering in the indigenous communities. Outsiders who are assisting members of the indigenous communities in this must take care to respect the unique cultural contexts and ethical considerations of the indigenous communities, in line with the policy of the Malaysian government.

Based on what I have seen in Malaysia, I think that students in urban areas need a breath of fresh air like their indigenous peers. There’s definitely a need for balance. I believe young people in urban areas should get out into nature to avoid overstimulation by technology. Meanwhile, students in rural areas should be given great access to digital resources, while taking care that their community values are not jeopardised. Cross-cultural exchanges and collaborations would provide opportunities for mutual learning and understanding, bridging the gap between urban and indigenous learning acquisition. Both paths have their merits and should be respected and fostered. By recognizing the strengths of each approach, we can create inclusive learning environments that honour diverse learning.

—

Shaida Salwi is currently the Head of Department for the Primary Unit, and an English educator at Victoria International School, Malaysia. She is also studying for an MA in English Literature at the University of Malaya. She is very passionate about female empowerment, children’s education and folklore. You may find her on Twitter @shaidaslwi

Shaida Salwi is currently the Head of Department for the Primary Unit, and an English educator at Victoria International School, Malaysia. She is also studying for an MA in English Literature at the University of Malaya. She is very passionate about female empowerment, children’s education and folklore. You may find her on Twitter @shaidaslwi

Yeonhee Sun is currently working as Youth Development Lead at The Prince’s Trust in the West Midlands, United Kingdom. She completed her MA in Education and Development from the University of East Anglia and has been involved in Rwandan adult literacy education through the Bridge Africa Project from the Korean National Commission for UNESCO. She also coordinated educational programmes with volunteers in Rwanda. Email: Yeonheesun1@gmail.com; Twitter: Yeonhee_Sun

Yeonhee Sun is currently working as Youth Development Lead at The Prince’s Trust in the West Midlands, United Kingdom. She completed her MA in Education and Development from the University of East Anglia and has been involved in Rwandan adult literacy education through the Bridge Africa Project from the Korean National Commission for UNESCO. She also coordinated educational programmes with volunteers in Rwanda. Email: Yeonheesun1@gmail.com; Twitter: Yeonhee_Sun

Janelle Rabe is a doctoral researcher at the Durham University Department of Sociology and a member of the Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA). Her PhD project is funded by the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership (NINE DTP) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). She has a decade of experience working with non-governmental organizations and policymakers in the Philippines on child rights and development issues. She has contributed to policy advocacy campaigns leading to the passage of laws on raising the age of sexual consent, child nutrition and child protection.

Janelle Rabe is a doctoral researcher at the Durham University Department of Sociology and a member of the Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA). Her PhD project is funded by the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership (NINE DTP) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). She has a decade of experience working with non-governmental organizations and policymakers in the Philippines on child rights and development issues. She has contributed to policy advocacy campaigns leading to the passage of laws on raising the age of sexual consent, child nutrition and child protection.