Katy Newell-Jones

In community development projects, people’s level of formal education often dictates their participation. I am interested in ways of creating learning spaces where these barriers are reduced.

I recently co-facilitated some knowledge sharing workshops on female genital cutting (FGC) in Samburu, Kenya. There were 20 participants from communities, local community-based organisations, two national NGOs and the local authority.

I recently co-facilitated some knowledge sharing workshops on female genital cutting (FGC) in Samburu, Kenya. There were 20 participants from communities, local community-based organisations, two national NGOs and the local authority.

Participants spoke a combination of Samburu, Masai, Swahili, English and French with no single, common language.

Some participants read and wrote with ease in more than one language. A handful, mainly men, had completed higher degrees. Most of the women and elders did not write at all.

The challenges

Initially, people deferred to those who spoke English confidently. Achievement in education was valued more than community experience. In groupwork, ‘educated’ participants wrote in English with complex sentences using development jargon.

As facilitators, we wanted all voices to be heard equally, to draw out the local wisdom, and to enable the voices of the women and elders to be heard. Two techniques helped achieve this, both required significant changes in the way the group worked.

Firstly, participants were encouraged to use whatever language they felt most comfortable with. This was particularly important as FGC is a sensitive topic, deeply embedded in local culture. I let go of my desire to understand the detail of the conversations. Translation became fluid with different people chipping in to help others, including me.

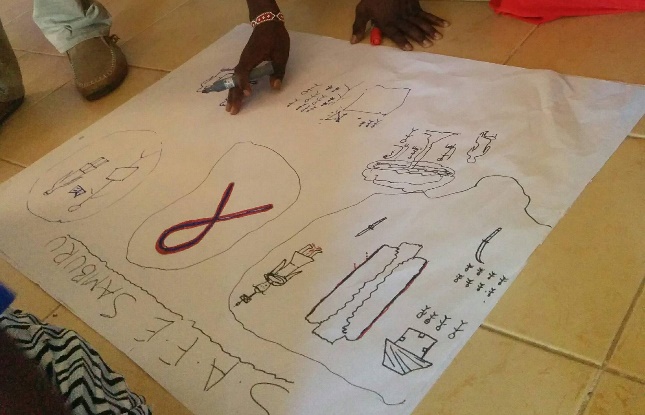

Secondly, pictures, diagrams and symbols were used on the flipchart, instead of text. Multiple coloured pens were available and creativity encouraged.

Changes

The discouragement of text was transformative.  The power within the groups changed. Those who were most comfortable writing were hesitant. Others, with some encouragement, came forward to sketch and draw, or to suggest images to illustrate complex ideas. Others added arrows, indicating the driving forces for and against change in their communities. There was no longer a right way of writing, or even a right way up for the flipchart paper, the communication of the ideas was what mattered. The discussion became less theoretical and more grounded in the complexity of FGC in the community. The groups became more chaotic with all involved, more disagreement and individuals arguing for their opinions to be portrayed.

The power within the groups changed. Those who were most comfortable writing were hesitant. Others, with some encouragement, came forward to sketch and draw, or to suggest images to illustrate complex ideas. Others added arrows, indicating the driving forces for and against change in their communities. There was no longer a right way of writing, or even a right way up for the flipchart paper, the communication of the ideas was what mattered. The discussion became less theoretical and more grounded in the complexity of FGC in the community. The groups became more chaotic with all involved, more disagreement and individuals arguing for their opinions to be portrayed.

When the groups gave feedback, participants were invited to interpret and discuss each other’s drawings. Plenary sessions were lively and participative. The women were more vocal and assertive. Participants took photos enthusiastically of each other’s flipcharts.

As the week progressed, the groups introduced a few key words on their flipcharts as well as images. These were written in different languages, often used alongside symbols and emerged organically.

Several of the participants who had originally avoided writing began writing individual words or names. Some copied them into their notebooks and a few began writing their own notes.

The range of literacy practices which were seen as ‘acceptable’ had been widened and more people felt able to contribute. Participants who had initially avoided any engagement with text had begun to feel sufficiently confident to experiment with their literacy practices and share them with others. Consequently, they felt heard and valued and in turn contributed more, both orally and using text.

During the evaluation participants said:

‘. . . it is right that pictures speak a thousand words. Drawings make us think more about what we mean. We do not just write but we have to discuss what we really mean first.’

‘Drawings are more important than writing. Even me who has not gone to school can draw. The community themselves can even do drawings.’

Several participants expressed their personal satisfaction at having written a few words, or having found they could read a few words. They said their self-confidence and self-esteem had improved, and they felt more able to engage in the dialogue around ending FGC in their communities.

Enhancing literacy practices was an unintended outcome. Two female participants said that they intended to continue to practise their reading and writing after the workshops.

In conclusion

Usually, when literacy is mentioned in community development projects the focus is on activities to improve literacy skills / practices. In this instance, the key was in recognising the barrier that formal literacy practices imposed on the knowledge exchange process. By reducing this barrier, and widening the range of literacy practices which were acceptable to, and valued by the group, more of the participants felt able to actively contribute, thus enriching the dialogue and in turn, the impact of the workshops.

With thanks to the people of Samburu and the Orchid Project which funded the workshops. You can read more on literacy friendly practices here.

The author:

Katy Newell-Jones has been actively involved in literacy since 1982, with a specific interest in working with NGOs in conflict and post conflict situations. She holds a National Teaching Fellowship from the UK Higher Education Academy and an honorary research fellowship with the Nuffield Department for Medicine, University of Oxford. She has been chair of BALID for over a decade and is about to hand over the role to Chris Millora.