Mohammad Naeim Maleki

University of East Anglia, UK and Herat University, Afghanistan

We as human beings are given the wisdom to live the way we prefer for our wellbeing. This enables us to choose what is best or reasonable for us. Under certain circumstances, this ability has placed us in a superior position compared to other creatures on the earth. Having this power and freedom of choice, we start preferring one thing over another from early childhood (e.g. children prefer candies to vegetables). We grow up facing many different circumstances that require us to decide; however, our decisions could be influenced by other factors around us. Therefore, as we age, we may become better decision-makers regardless of our education level. Although ‘non-literate’ people might not be able to read or write properly, research has shown that they come to class with plenty of life experiences as decision-makers which should be recognised by educators and facilitators.

Researching decision-making dates back many decades. Many research studies have focused on decision-making in critical situations such as in the military, medicine and in the firefighting contexts[1], with some studies in educational contexts as well. For example, Cox and Robinson-Pant (2010) explored school children as decision-makers and Seo et al. (2016) investigated adults’ decisions considering their health literacy.

It cannot be ignored that adults are decision-makers in their everyday life. Depending on their different roles and identities in their daily interactions, they have been deciding on a variety of matters at different levels both for themselves and for their family members and friends around them. For instance, parents decide which schools their children should go to; a father/mother decides how much of his/her income should be spent on what and how much should be saved; a mother decides whether to breastfeed her child or not; a shopkeeper decides what products he/she should put on sale. When these adults come to an education context such as literacy classes, they still hold their identities as a father, a mother, a shopkeeper etc. and are still decision-makers outside the classroom. However, in my research I found that some facilitators forget the fact that their learners are decision-makers at home and treat them like school children in the adult literacy classroom.

On the other hand, we should not ignore the limitations to our decision-making as well. Although at the end it would be the father, mother, shopkeeper and so on who takes the final decision, they are bound by their surroundings, their personality, their context and culture. For example, a breastfeeding mother’s decision might be influenced by the local customs, by her husband’s/family’s decisions or even by the child. This inter-dependency determines the freedom of choice for adults.

Decision making has been explored in many different ways. Kabeer (1999) relates the use of choices in decision-making to individuals’ agency and sees it as “people’s capacity to define their own life-choices and to pursue their own goals” (p. 438). But can decision-making be summarized as having or not having choices? In real life situations, for example, Oraranu and Connolly (1993) mentions “decisions are embedded in larger tasks that the decision-maker is trying to accomplish” (p.6). The tasks may constitute the goals which could be achieved if the person has access and control over those choices.

Furthermore, these circumstances and experiences may make the adults better decision-makers. As Moll et al. (1992)states, adult learners come to class with ‘funds of knowledge’ which they have developed unconsciously and unintentionally; it could be, as Rogers (2015) says, “like breathing, something we all do without thinking about it except occasionally” (p.261).

Coming to a class with ‘funds of knowledge’ adult learners have some degree of control over the programme either consciously or unconsciously. For example, it is the adult learners who decide to come to the class late or leave early, to write their assignments or not, to do the drilling activities or not which could have an influence on the flow of the lessons. So, they decide on their own (with the influences from the context or others) to do or not to do certain tasks related to their learning process. Therefore, considering their choices in planning and delivering literacy services is prominent in designing these programmes. The other significant point is the implication of learners as decision-makers on policy and practice. This requires another blog; it could be also discussed in the comments below.

[1] See Klein, G. A., Calderwood, R, & Clinton-Cirocco, A. (1986). Rapid decision making on the fire ground. Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 30th Annual Meeting, 1 , 576-580.

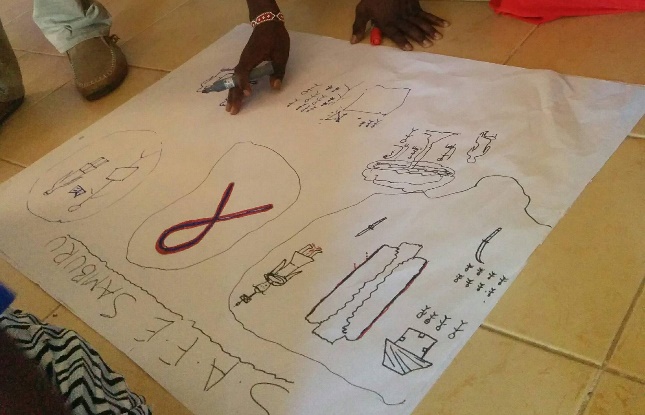

The power within the groups changed. Those who were most comfortable writing were hesitant. Others, with some encouragement, came forward to sketch and draw, or to suggest images to illustrate complex ideas. Others added arrows, indicating the driving forces for and against change in their communities. There was no longer a right way of writing, or even a right way up for the flipchart paper, the communication of the ideas was what mattered. The discussion became less theoretical and more grounded in the complexity of FGC in the community. The groups became more chaotic with all involved, more disagreement and individuals arguing for their opinions to be portrayed.

The power within the groups changed. Those who were most comfortable writing were hesitant. Others, with some encouragement, came forward to sketch and draw, or to suggest images to illustrate complex ideas. Others added arrows, indicating the driving forces for and against change in their communities. There was no longer a right way of writing, or even a right way up for the flipchart paper, the communication of the ideas was what mattered. The discussion became less theoretical and more grounded in the complexity of FGC in the community. The groups became more chaotic with all involved, more disagreement and individuals arguing for their opinions to be portrayed.