Malini Ghose and Theresa Frey

BALID and the UNESCO Chair in Adult Literacy and Learning for Social Transformation have been hosting a series of blog conversations following up on the discussions at the 4th Brian Street Memorial Event on the theme ‘decolonising literacy’. Taking ‘decolonising literacy’ as our starting point, we will explore and extend some of the questions raised by Brian Street around power, voice, identity and literacy: ‘Where are people going if they take on one literacy rather than another literacy? How do you challenge the dominant conceptions of literacy?’

Read the introduction blog here. The second instalment of the series is here and the third instalment is here.

—

At the Brian Street Memorial Lecture Malini Ghose shared and reflected on the LETTER Writing project conducted in 2005. Malini and Theresa Frey (PhD researcher at the University of East Anglia) discussed the LETTER Project and how it still resonated with Malini today personally and as a practitioner and a researcher.

Malini: In 2005, I observed during the LETTER Project that literacy is closely tied to the complexities of everyday lives and the complicated nature of how we articulate aspirations. Women want to be schooled in dominant literacies even when they know they may not be able to use their skills. Saying they want to learn how to read the bus number when there is only one bus that passes by their village. A “surface” reading does not allow you to delve into the inner working of literacy and the meanings they hold for people.

Literacy is always a matter of power. Our research and practice should interrogate the larger field of power relations within which literacy may be embedded. We should expect to be surprised at the different meanings people ascribe to literacy(ies) as these are continuously being constructed and re-constructed. We need to go beyond the binaries that we tend to create in our literacy research, policy, and programme frameworks, such as Literate vs illiterate, Dominant vs local literacy practices, Oral vs written or text vs visual literacies.

I still see a value in training practitioners, facilitators, advocates, and policymakers to “see” and understand the power relations embedded in everyday lives and validating local practices. And more importantly, to try and bring those into the classroom through the pedagogies they use and the materials they may develop.

Theresa: I appreciate your reflection on the LETTER Project and the continued work on challenging literacy(ies) practices. How do you use a feminist lens in these literacies practices/events?

Malini: As a feminist practitioner, I am concerned about negotiating and realigning unequal gender relations through literacy teaching and learning. Let me give you one example.

During our research, we would often walk around the village just observing what texts were available in the environment, what men and women were doing etc. In the afternoons, we would inevitably come across groups of men playing cards. This observation became a point of discussion with the facilitator-researchers. Was “card playing” a numeracy event, and if so, what broader field of power relations was this located in? Many facilitators said that this was a “bad habit” that only men engaged in. Women were essentially “good” and therefore did not play cards. But we probed further ¬– could it also be that only men played cards was because women were systematically excluded from the public sphere? Or at best they could participate in ways that were prescribed and socially sanctioned? Playing cards or publicly having fun was not one of these. Many of the facilitators then revealed that they had secretly desired playing cards but were too scared to express this.

However, when we (researcher-curriculum developers) suggested that we include a card-playing session in class as a way of learning numeracy, this was met with incredulity and resistance. But we went ahead. And it proved to be not just a way of teaching a range of numeracy skills but simultaneously challenged several gender norms. This was not to suggest that women should start playing cards or that gambling was not a very real problem that women encountered, but it did open up discussions on a range of other gender issues. It helped to transgress entrenched gender norms in a non-confrontational way. Occasionally playing cards did not make you a “bad woman”, and girls could occasionally have fun, even as they learnt to read and write.

For me, a “feminist lens” means putting women’s experiences and their perspectives – their ways of being and seeing — front and centre while documenting and analysing the larger field of power relations within which literacy is located.

Theresa: I remember you discussing your work utilising the ‘empowerment’ approach. How did you use the ‘empowerment’ approach to ensure you did not lose the learners voices?

Malini: Working with an “Empowerment” framework, even though it is believed to be a progressive and a “critical approach” to literacy, comes with its own challenges. This comes back to the binary issue of empowerment vs disempowerment.

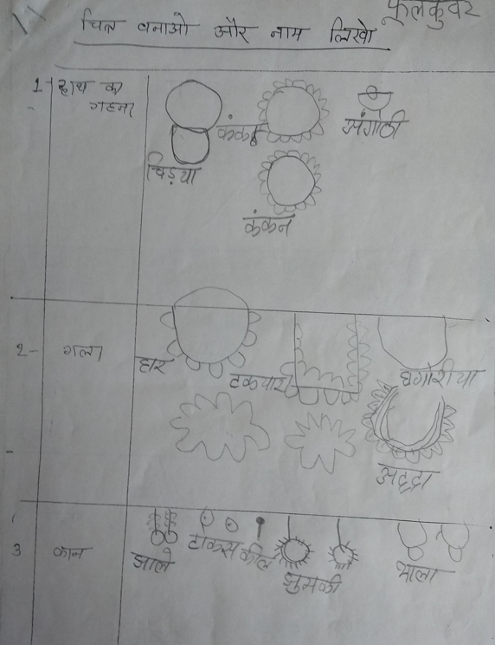

There is little recognition that women, even if they are economically “poor”, actually lead “rich” lives. There are songs, music and stories in their lives as well. They have knowledge that they can teach the experts. Interaction with learners about rituals and traditions led to a discussion about jewelry. Soon there was an outpouring of different types and names of jewelry that women wore on different parts of their bodies. Each piece of jewelry was linked to stories, rituals, aesthetics, designs, and who could wear what jewelry, which was related to social issues of caste discrimination, debt and widowhood. This was eye-opening for me. However, a discussion on jewelry would never find a place in a literacy primer.

What I learnt was that as so-called experts, we needed to step back from our own affirmed positions, observe, listen and not accept simplistic “assessments” of learner needs. We needed to continuously relook at our approach and materials to try (it is not easy) and ensure that women learners are speaking for themselves.

—

Malini Ghose is one of the founder members of Nirantar. She has worked in the field of education and women’s rights for nearly 30 years in various capacities – as a grassroots practitioner, trainer, material and curriculum developer, researcher, and activist. She has helped design and implement various innovative education programmes for women, and reviewed and provided technical inputs to government, NGO interventions and international projects. Her articles have been published in various journals. She is presently completing her PhD at the University of Göttingen, Germany.

Malini Ghose is one of the founder members of Nirantar. She has worked in the field of education and women’s rights for nearly 30 years in various capacities – as a grassroots practitioner, trainer, material and curriculum developer, researcher, and activist. She has helped design and implement various innovative education programmes for women, and reviewed and provided technical inputs to government, NGO interventions and international projects. Her articles have been published in various journals. She is presently completing her PhD at the University of Göttingen, Germany.

Theresa L. Frey is a PhD student at UEA whose research aims to examine ‘Education Experiences for Asylum Secondary Students Resettled in New York City, United States’ through an ethnographic study using participatory approaches. She has 17 years of higher education and international non-profit experiencesincluding director of education abroad, an elementary teacher for refugee children, international faculty director, art-based learning for children, international prestigious fellowships advisor, global health and safety trainer, and intercultural communications facilitator. She has research experience in Afghanistan, Jordan, Greece, and Italy and teaching in Costa Rica and the United States.

Theresa L. Frey is a PhD student at UEA whose research aims to examine ‘Education Experiences for Asylum Secondary Students Resettled in New York City, United States’ through an ethnographic study using participatory approaches. She has 17 years of higher education and international non-profit experiencesincluding director of education abroad, an elementary teacher for refugee children, international faculty director, art-based learning for children, international prestigious fellowships advisor, global health and safety trainer, and intercultural communications facilitator. She has research experience in Afghanistan, Jordan, Greece, and Italy and teaching in Costa Rica and the United States.