Zubair Torwali

Idara Baraye Taleem wa Taraqi, Pakistan

Twenty years ago, in November 2002, a symposium was held in Kyoto, Japan, under the auspices of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) where a group of experts named as UNESCO’s Ad Hoc Group on Endangered Languages worked on a document entitled ‘Language Vitality and Endangerment’, which was published by UNESCO in 2003. This document lists nine factors in language vitality including:

1) Intergenerational language transmission,

2) Absolute number of speakers of the language,

3) Proportion of those speakers within the total population,

4) Trends in use of the language in existing language domains,

5) Response to emerging domains and media,

6) Materials for language education and literacy,

7) Official status and use including institutional and governmental policies,

8) Community members’ attitude toward their own language and;

9) Amount and quality of documentation.

All these factors are integrated and related to each other. Government and institutional policies affect the community’s attitude toward their own language, which further impacts intergenerational transmission, community response to new domains and media including the production of materials for language education and literacy. Government policies greatly impact the availability of materials for language education and literacy directly as well. The quality and amount of documentation influence literacy materials in a direct way, too, for no literacy materials in a language can be produced without documentation. Traditionally, documentation is text oriented as suggested by Prof. Himmelmann in his work on documentary linguistics. Many linguists follow the contrast he makes between language description on the one hand and language documentation “characterized as radically expanded text collection” on the other (Himmelmann, 1998, p. 2)

In a society like ours in Pakistan, where education is limited and mostly held as writing and reading of a certain language – in other words, conventional literacy – text still dominates, and great prestige is attached to it. In our Pakistani context a ‘language’ is what is written whereas the general perception holds that any language, not in writing, is a ‘dialect’ meaning speech but devaluing the language.

Given this particular educational and social context we had to first bring our languages into writing and promote their literacy with primary focus on its writing and reading. The writing systems of most of the indigenous languages in North Pakistan including my language , Torwali, were developed after 2000 CE.

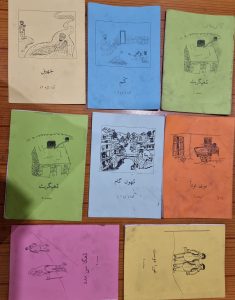

I began to develop the first ever alphabet book of Torwali in 2004 and after two years I, along with a team of other Torwali activists, started to develop a curriculum and course books in Torwali for the multilingual education (MLE) schools which started in 2008. This was after we had developed the course books for the literacy and non-literacy subjects. We got our preliminary training from the Frontier Language Institute , which is affiliated to SIL International and is now named the Forum for Language Initiatives (FLI), based in Islamabad, Pakistan. Since 2008 our Torwali MLE schools, now called the Innovative Learning Model Schools, have grown to four in four different locations and the higher grade now is grade four.

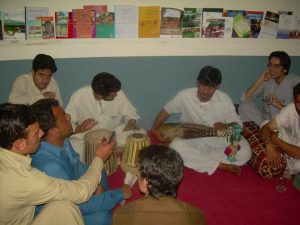

Forced and motivated by the interplay of all the language vitality factors, we have tried a holistic approach to overall language literacy and development. Our organization, Idara Baraye Taleem wa Taraqi (IBT) which we established in 2007 has since then undertaken many integrated activities along with the MLE schools which include holding cultural and musical festivals, producing materials in Torwali for adults, developing literacy among the Torwali women, advocating for the cultural and other rights of the community, conducting research in Torwali people’s history, reclaiming and strengthening the ‘Torwali’ identity. These activities helped in changing the community’s attitude toward their language and culture, built their self-esteem, fostered greater self confidence among the youth and made the community recognized among the dominant communities. We also made greater use of social media and conventional media to promote Torwali, its culture and identity.

The Torwali language revitalization program is greatly acclaimed in Pakistan and internationally by academics, activists and the media. Our model fits into what Mary Kalantzis and Bill Cope suggest in their book ‘Literacies’ (2012) as a ‘Multi-contextual and multimodal’ approach to literacy instead of the conventional literacy which focuses on the ‘textual formalities such as correct spelling and grammar’.

We have also been facing many challenges including the use of digital media in enhancing the Torwali language. Our current donors have also refused to extend funding our program beyond June 2023. This is undoubtedly the biggest challenge we now face: how to sustain our Torwali MLE program for the children as well as continuing the overall Torwali literacies and language development work.

—

Zubair Torwali is a writer and activist for the rights of all the marginalised linguistic communities of north Pakistan. He is the founder of the civil society organisation Idara Baraye Taleem wa Taraqi, and the author of Muffled Voices: Longing for a Pluralist and Peaceful Pakistan (2015), among others. He lives in Bahrain, Pakistan. He has been working for increasing literacy of the endangered languages of North Pakistan.

Zubair Torwali is a writer and activist for the rights of all the marginalised linguistic communities of north Pakistan. He is the founder of the civil society organisation Idara Baraye Taleem wa Taraqi, and the author of Muffled Voices: Longing for a Pluralist and Peaceful Pakistan (2015), among others. He lives in Bahrain, Pakistan. He has been working for increasing literacy of the endangered languages of North Pakistan.

References:

- Himmelmann, N. (1998). ‘Documentary linguistics and descriptive linguistics’. Linguistics, 36, 161–195.

- Kalantziz, M. & Cope B (2012). ‘Literacies’. New York: Cambridge University Press.